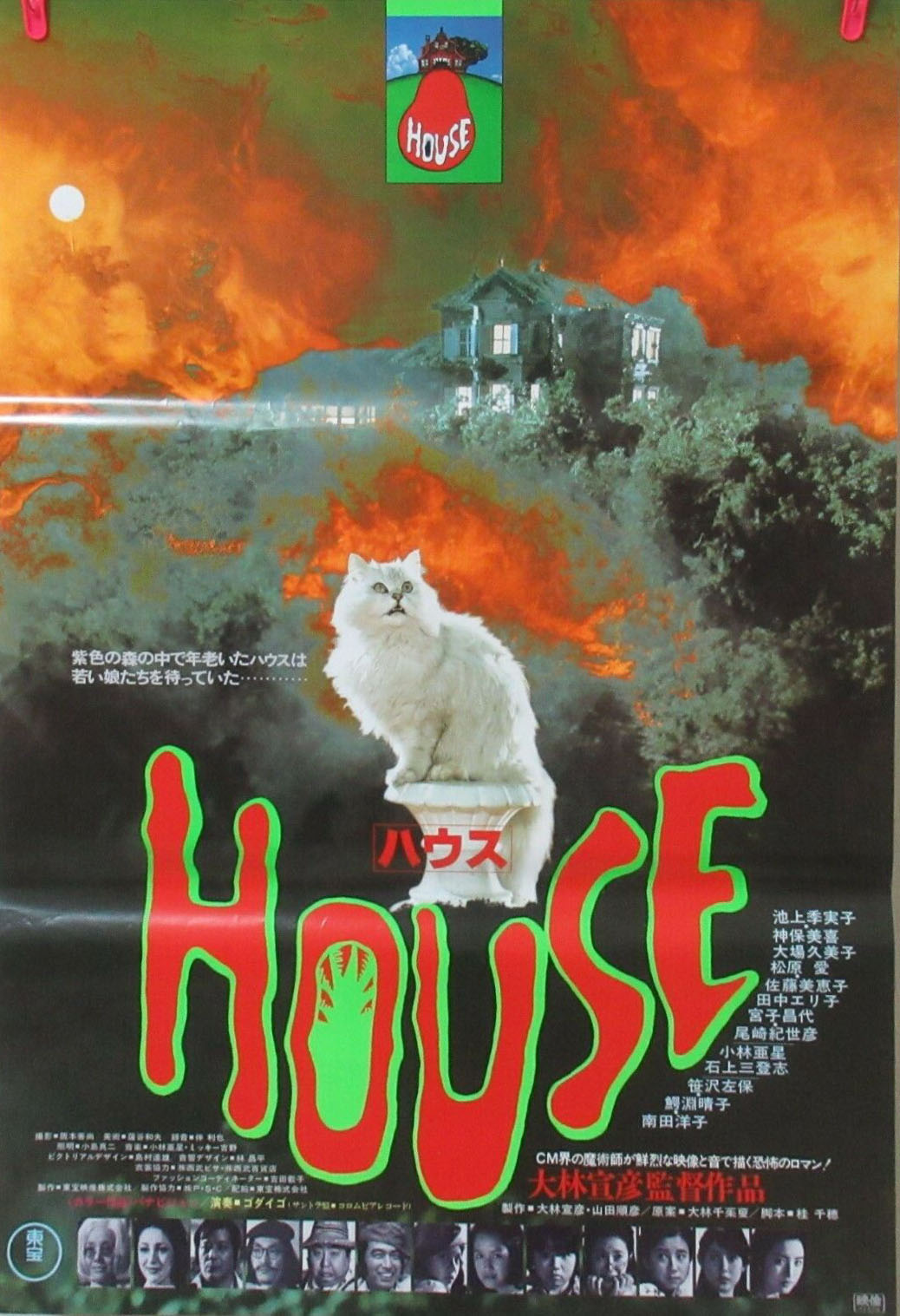

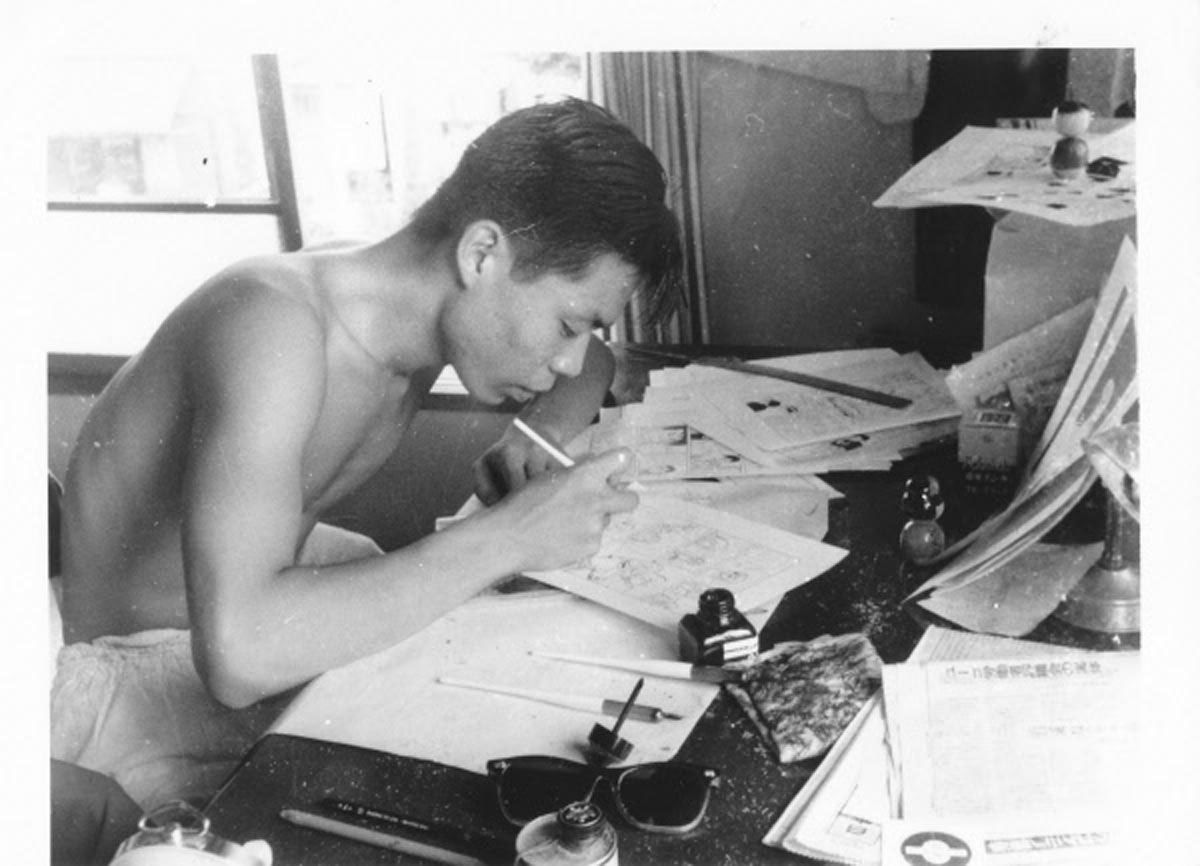

“House (Japanese: ハウス, Hepburn: Hausu) is a 1977 Japanese experimental comedy horror film directed and produced by Nobuhiko Obayashi. It stars mostly amateur actors, with only Kimiko Ikegami and Yōko Minamida having any notable previous acting experience. It is about a schoolgirl traveling with her six classmates to her ailing aunt’s country home, where they come face to face with supernatural events as the girls are, one by one, devoured by the home.”(wiki)

After writing about Josephine Decker’s last movie – The Sky is Everywhere and mentioning in passing the Japanese horror cult movie House – known as Hausu for all its fans (i feel indebted here to the artist-in-residence at Utopiana/Geneva that introduced me to this wonderful and delightful movie a few years ago). If you did not see it yet, watch it, it is a must! Needless to say I feel a lot of welcome aesthetic kinship here (to Decker’s recent movie), including hints of visual virtuosity and lack of inhibitions about employing varied animation techniques.

I am happy to recommend this piece of utter playfulness and I cannot express my sincere appreciation to everyone who participates in such cinematic transmedia explorations, especially weirdly horrific ones.

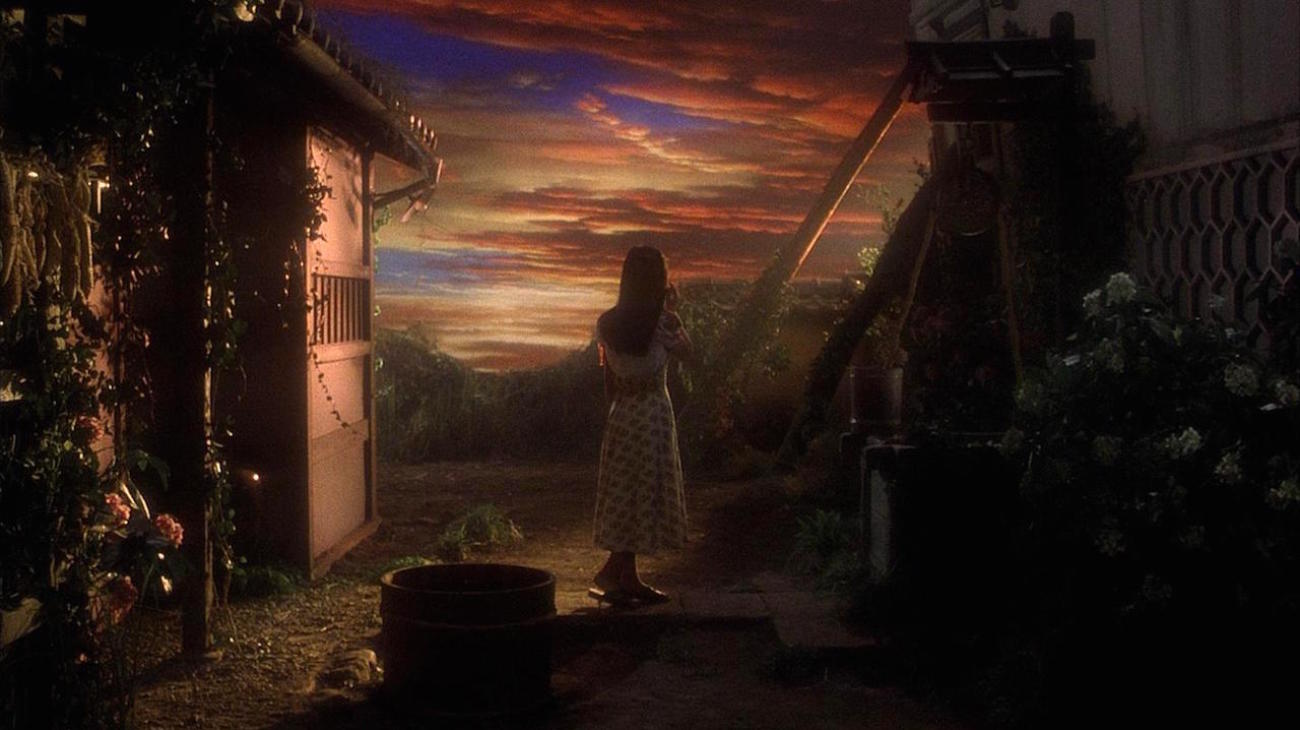

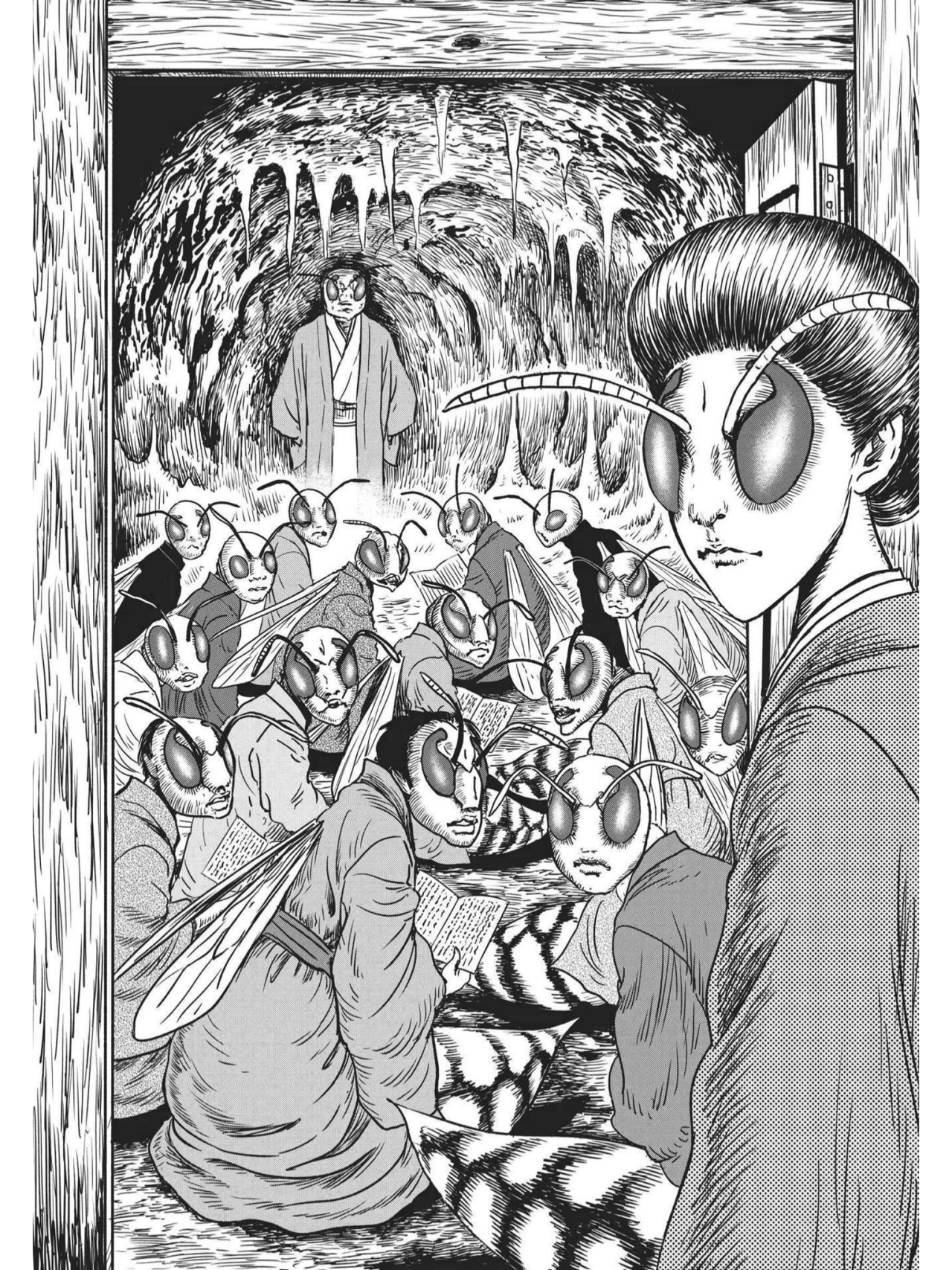

Without giving too much away, this is not a very ‘Japanese’ horror, none of the spirits, none of the yokai appear, or at least when they appear they seem perfectly Europeanized. That being said there is a lot of animation – parts frolicking around and objects having an agency of their own. As I have recently started reading an important new book by Sonam Kachru about other lives and different modes of being (including dreaming one) – inspired by a well-known Buddhist philosophy text from the V century (the Twenty Verses of Vasubandhu), I find a certain sensitivity here or disponibility to include more than just the waking life or just the ‘normative’ mindedness or normal touch/feel of what is considered typical of (human) lives and recognize the importance of thinking with very different and alongside less-than or more-than human creatures from very different (habitats) worlds than ours (such as the Buddhist hell worlds or the hungry ghosts – in Vasubandhu’s key thought experiments). I find this 1977 movie very helpful in imagining or including the life of quite different creatures (than ourselves) that stray from ‘our’ world and get housed in this delightful movie using these varied techniques.

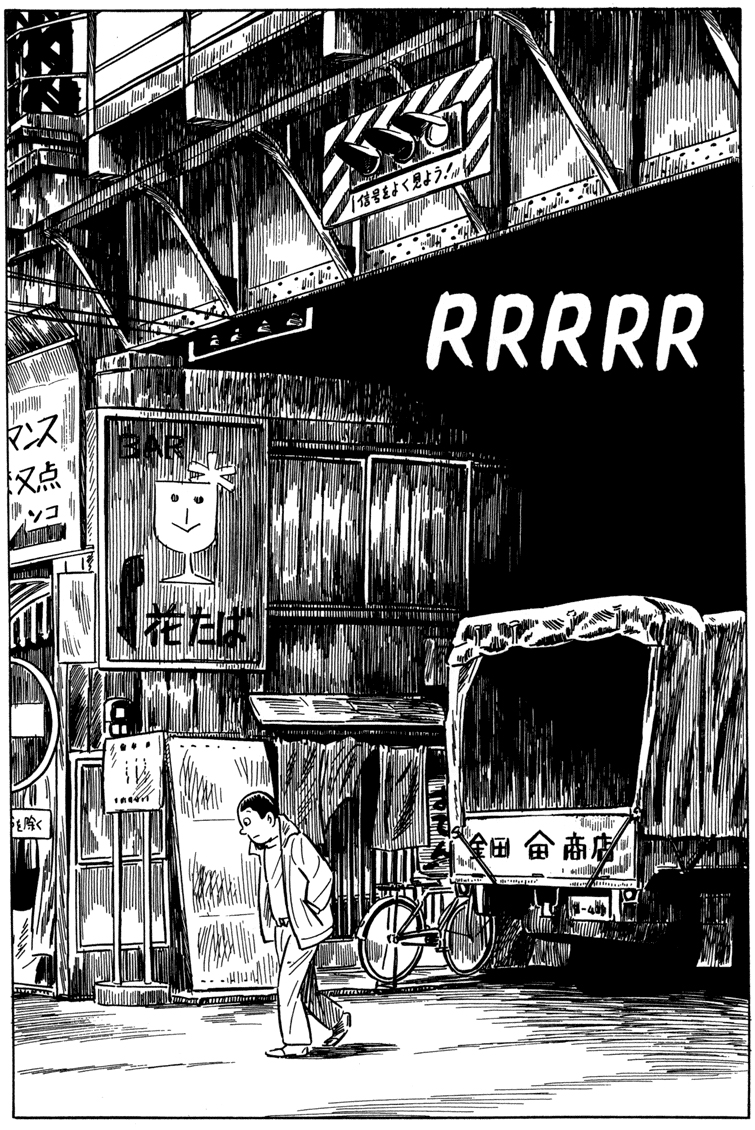

On one side it is an anti-horror movie and on the other it shows how stuck we are in adopting the same settings or horror aestethics . The experimental wacky way in which it treats horror even body horror is unique – there is something both cartoonish, schematic, a touch of anime and also avantgarde and even ill-mannered dark psychedelia to it. After beheading human heads bite you in the ass, cats are fierce growling spirits with laser eyes, pianos are slaughterhouse machines. Overall it is a genre-defying movie in a category all of its own.

It is both colorful, baroque, gory, wonderfully kitschy and completely exaggerated screwball and gruesome at the same time. It is like a Grand Guignol turn of the 1900 decadent spectacle transformed into a movie. It goes to the origins of cinema in freak shows and gore theatres and also points to its future as a bastardized FX carnival of souls.