timespace coordinates: 2021 mountain valleys and backwoods hiking trails

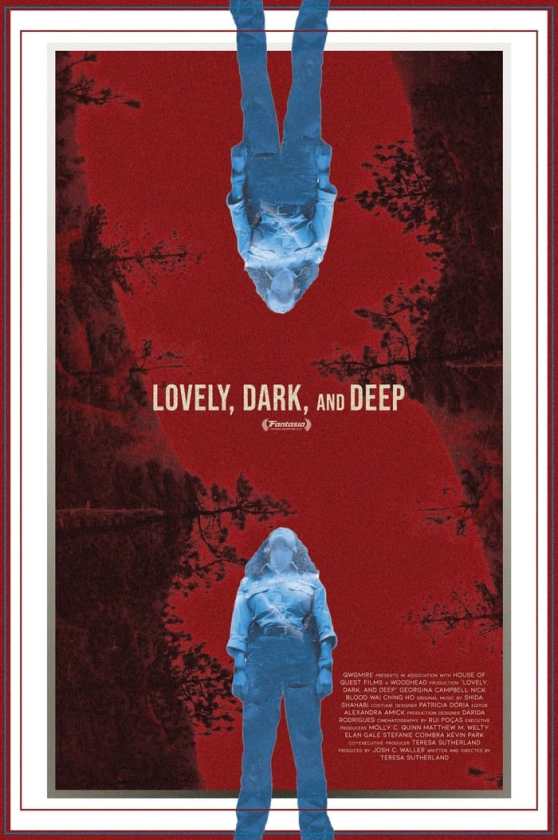

Lovely, Dark, and Deep is a 2023 American horror film written and directed by Teresa Sutherland in their feature length debut, and starring Georgina Campbell. (wiki)

timespace coordinates: 2021 mountain valleys and backwoods hiking trails

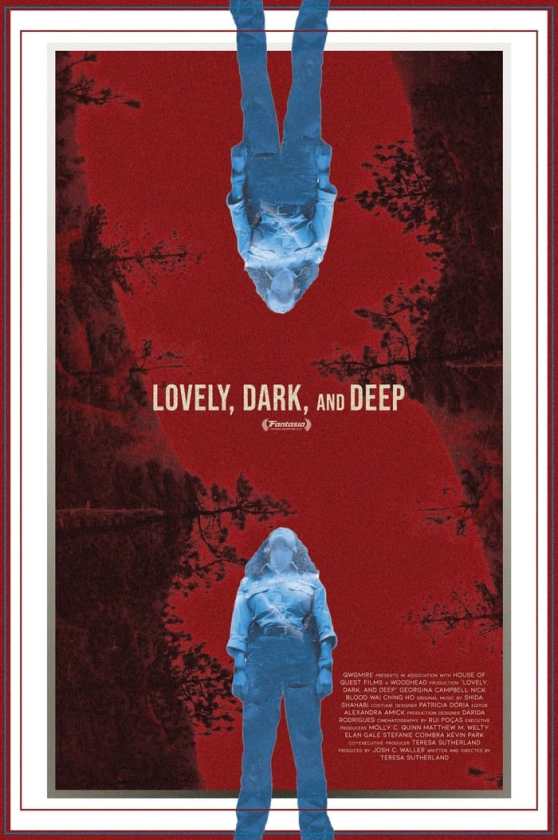

Lovely, Dark, and Deep is a 2023 American horror film written and directed by Teresa Sutherland in their feature length debut, and starring Georgina Campbell. (wiki)

timespace coordinates: 1973 on an uninhabited island off the Cornish coast

Enys Men (Cornish for ‘Stone Island’) is a 2022 British experimental folk horror film shot, composed, written and directed by Mark Jenkin. Shot on 16 mm film, it stars Mary Woodvine, Edward Rowe, Flo Crowe and John Woodvine. (wiki)

timespace coordinates: 1960s Massachusetts, the story trails the relationship between two women working at a juvenile detention facility

Eileen is a 2023 psychological thriller film directed by William Oldroyd, based on the 2015 novel of the same name by Ottessa Moshfegh who co-wrote the screenplay with her husband Luke Goebel. It stars Thomasin McKenzie, Shea Whigham, Marin Ireland, Owen Teague, and Anne Hathaway. (wiki)

“One of the most acclaimed Eastern European directors of the late 1960s, Miklos Jancsó became known for his abstract long-take style which explored the intersections of power, politics, history, and myth. (“Radical form in the service of radical content,” as the Village Voice film critic, James Hoberman, put it back then.) Now that the Beacon Cinema in Columbia City is hosting a retrospective of six of his films (including Red Psalm, which won him the best director prize at the 1972 Cannes Film Festival), Red May has invited three film scholars–Eszter Polonyi, Zoran Samardzija, and Steven Shaviro—to discuss Jansco’s boldly stylized film language with Tommy Swenson, Film Curator of the Beacon Cinema“. (YT channel)

Among the films by Miklos Jancsó discussed:

The Round-Up (1965) The Red and the White (1967) The Confrontation (1968) Winter Wind (1969) Red Psalm (1971) Electra, My Love (1974) as well as many of his later (ignored by the Western film publics and critics) from the 80s and 90s.

As a person from the former East – I find it both satisfying at the same time – when one of the most important film directors to have come from Eastern Europe gets the due recognition and sparks such fruitious exchanges as the above (hosted by Red May red arts, red theory, and red politics show from Seattle) – and also frustrated by the fact that his movies are tough to find/watch on the net. I am also emboldened to post this here – as we live at a time where the East and West left seem irredeemably split around Russia’s aggression of Ukraine. There are many receptions of his Jancso’s films – both in the West (in France in particular) as well as different reception in the West than from his native Hungary (as Eszter Polonyi makes amply clear above). It is impossible to give due attention to all what’s been discussed above but here are are some attempts:

timespace coordinates: India 21st century

“The Disciple is a 2020 Indian Marathi-language drama film written, directed and edited by Chaitanya Tamhane.[2] It stars Aditya Modak, Arun Dravid, Sumitra Bhave, Deepika Bhide Bhagwat, and Kiran Yadnyopavit. Alfonso Cuarón serves as an executive producer.[3] It was entered into the main competition section at the 77th Venice International Film Festival, becoming the first Indian film since Monsoon Wedding (2001) to compete at the festival.

Sharad Nerulkar has devoted his life to becoming an Indian classical music vocalist, diligently following the traditions and discipline of old masters, his guru, and his father. But as years go by, Sharad starts to wonder whether it’s really possible to achieve the excellence he’s striving for.” (wiki)

There is a lot of reasons one might watch this movie – it offers a good break from the usual – self-absorbed Euroamerican world (this has become a leitmotif of recent posts here it seems). There’s constant talk about New World Order and it’s telling that the Western world (led by the US) has become united against Russia’s aggression and there’s been wide protest against of the war in Ukraine in particular. This in turn produced something without precedent to my knowledge – the final rush to switch or transition from fossil fuel dependency (in view of Europe’s and especially Germany’s dependency on Russian gas as well as oil and coal) to green energies. As this takes time and there’s always the German petroleum lobby and powerful car manufacturing industry to weight in their interests (in spite of what everyone thinks) – the ironic one sided result might be a reinforcement of Saudi Arabia/UAE oil producers, already big buyers of Western weapons (Germany and France have been selling weapons in the Yemeni Civil War in what is considered the biggest humanitarian crisis of the century). India has been a surprise so far since it parted ways with the other members of the QUAD alliance on the issue of Ukraine, being part of the small (just 4 countries ) group of governments at UN that didn’t call Russia aggressor.

Since a few years, there is a new specter of economic nationalism as a result of general dissatisfaction with globalism inequalities and lopsided effects. Yet the two – centrifugal & centripetal forces ae interdependent, two faces of the same coin. Both India and China have abstained from the unanimous condemnation of Russia and this poses several problems. I don’t want to make a bigger case here – but I try to emphasize it is good to keep an eye and mind open to (ignored or transformed into the big other) large parts (&most populous) of the planet that are being excluded from our daily reality in the extended West (speaking now and writing from Berlin, Germany) or the ones that the global North has been labeling ‘broken’, ‘rogue’, ‘the end of history’, ‘integrated’ etc. This 1989 history is always being forgotten or pasted over with incredibile duplicity. There is always a lot of ‘missing’ – coverage of people living and existing elsewhere. How does one relate to such non-existing images – the scarcity of other represented realities, other lives and places?

What Disciple offers is a small sample of another world and another life – nothing from the past but a contemporary world to ours, one that is neither idealized nor exoticized. The movie is a slow burner, what’s been called ‘slow cinema’ (which I do not indulge in very often) at its best. It is a series of tableaus of concerts of classical Hindustani music (i will not go into detail since I do not want to make blunders nor pretend knowledge in this area). I have had previous contact with Indian music tradition via friends and mediators. There is today a translational and international scope of this Hindustani musical tradition that was made familiar (in the West) by phenomenal instrumentalists such as Ravi Shankar and Ali Akbar Khan from the 1960s on. Following the growing Indian diaspora, Hindustani music has achieved recognition everywhere and patrons as well as students from outside its initial range of dispersal and far more from its original classical origins. Classical music – wasn’t just Bach & Co, but various other non European traditions.

I like the frankness of this movie – it is really an amazing piece of cinema (not just because it has been nominated for prizes). It presents some incredible encounters with both disciple-master relations and with current striving for skill & perfection (or lack of understanding of what others consider important), a path of austerity, exercices and a whole new range of expert knowledge. I enjoyed the sense of joyless dedication (there’s does not seem to be the usual success – or Euroamerican cheering) for something quite elusive, yet also the absence of major distractions, even the scenes of mastuebation. One is exercising on and on with consummate dedication even if one keeps failing. From archival precious materials of tapes or highly specialized traditions and even masters who refuse recordings and who show us a very different facette, an anti-spectacular form of performativity. Maai – the legendary singer mentioned is a representative of Khyal tradition – (ख़याल) that is a major form of Hindustani classical music in the Indian subcontinent.

With The Disciple one can say that one enters for a short while a different world of sound – and improvisation. There is a lot of hard lessons there for us and for the eponymous disciple. A lot of the time it is not even clear why such sacrifice is included in his practice. I liked the presence of the online – and also of the whole analog tape collector mania. There is also a fine sense of irony when actor Aditya Modak encounters one such famous collector-expert that somehow smashes all his idols and provokes in him a rare show of violence. I also like the time passage and how time is measured in this movie.